Argentina President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner warns voters that they stand to lose everything they gained under 12 years of government by herself and her late husband if they vote for the opposition. Her approval ratings show that half the population buy into that narrative even as the reliability of the country's economic data has been questioned by the International Monetary Fund and private economists. Her party's candidate failed to secure an outright victory in Argentina's presidential elections on Oct. 25 and was forced into a runoff vote later this month.

In these five charts, we try to separate fact from fiction.

Economic growth

Nestor Kirchner inherited a country in a mess when he took power in May 2003. Less than two years earlier, Argentina had defaulted on $95 billion. South America's second-biggest economy was in the throes of an economic crisis as reserves dried up and the government was forced to exit the one-to-one peso-dollar convertibility currency system that lowered inflation. The subsequent devaluation — the peso fell to about 3 pesos per dollar and today trades around 9.5 to the dollar — and inflation eroded purchasing power and threw people out of work and into poverty.

But Kirchner was also blessed with rising soybean prices. With the boost in grain exports, which account for more than a third of Argentina's export revenue, the country's economy began to grow at a fast clip during Kirchner's time in office and Fernandez's first term. High exports allowed the government to post both a trade and a fiscal surplus, but as the boom slowed, those surpluses have shrunk and the government has had to cut back on imports, affecting manufacturing, and has struggled to finance the consumption that propelled growth.

As the economy slowed and inflation rose, economists noticed inconsistencies in the government's data reporting. Suspicions that the government was manipulating data were aggravated when in early 2007 Kirchner replaced a officials in the national statistics agency, known as Indec. Chart 1 shows a comparison between the official monthly economic activity index, a proxy for gross domestic product, and an index created by economic-research firm Elypsis that uses indicators it believes are still trustworthy.

The gap between official and private estimates shows how the government began to understate the troughs and exaggerate the peaks, according to Luciano Cohan, chief economist at Elypsis.

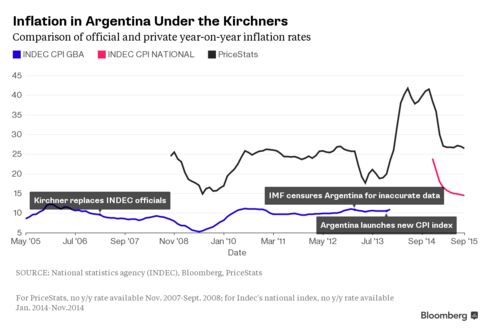

Inflation

The disparity was more pronounced when it came to reporting inflation. It became so disproportionate that in February 2013 Argentina became the first nation to be censured by the IMF and was told it faced sanctions if it didn't correct its ways. The government responded in early 2014 by launching a new nationwide consumer price index and announced a new base year for calculating the GDP index. While results on both indexes were initially close to private estimates, the discrepancy has widened once again.

Poverty

It's a similar story when it comes to poverty. Almost half of Argentines were poor when the Kirchners came to power and both official and private estimates concur that the levels have been slashed considerably. While the government stopped publishing the poverty index at the end of 2013, saying it would need time to recalibrate it after starting the new inflation index, Fernandez in June said the rate was below 5 percent and her cabinet minister claimed Argentina has lower levels of poverty than Germany.

Since 2007, the Center for Research and Studies of the Republic of Argentina, a research unit of a umbrella group for Argentina's unions, has used an average of inflation estimates from nine provinces to calculate its own poverty index. It says poverty levels reached 17.8 percent in 2013. Another independent measurement of poverty carried out by the Catholic University of Argentina estimates poverty levels at 28.7 percent of the population.

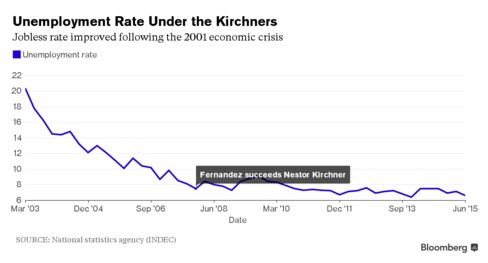

Employment

When the Kirchners assumed power 12 years ago, unemployment levels were above 20 percent. With the economic recovery that followed, they were able to boost job growth. The jobless rate is the lowest in more than 25 years. Critics say the fall is explained by a concurrent drop in the rate of the economically active population, which measures the number of people employed or actively seeking work, suggesting there are fewer people seeking employment, either by taking early retirement or delaying entering the workforce due to government subsidies, said Daniel Sticco, director of the Institute of Labor and Social Studies at the University of Business and Social Sciences.

The numbers are also boosted by a rise in public sector employment under the Kirchners. Since 2003, state employment has increased by 60 percent to 3.5 million people, or about a fifth of the total workforce, according to the Latin American Economic Research Foundation, or FIEL.

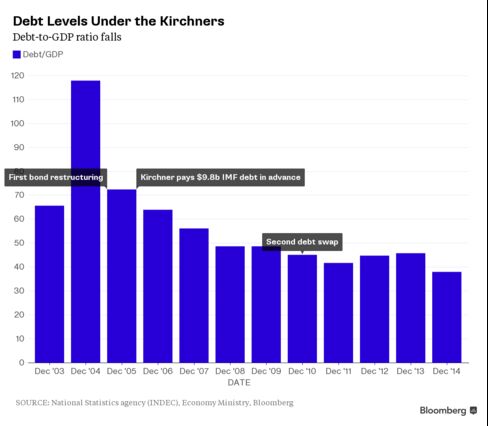

Debt

The Kirchners came to power in the wake of the biggest default in history. They rallied Argentines behind them by criticizing the levels of debt the nation accumulated during the 1990s and set out to reduce them through negotiations with bondholders to restructure the defaulted securities. They persuaded creditors to accept a 70 percent discount and paid off $9.8 billion in debt owed to the IMF. At her state of the union speech in January, Fernandez was able to claim she would be leaving a country "free of debt."

It will be, perhaps, the Kirchners' most enduring legacy. Whoever wins the Nov. 22 second round — ruling party candidate Daniel Scioli or the opposition's Mauricio Macri — they will be able to count on ample space to issue credit to help them tackle the litany of economic problems they will inherit.

—With reporting by Aansh Mehta.