Bond investors have been snapping up Argentine bonds on optimism the nation’s next president will end a dispute with creditors. But there’s one debt security they’ve shunned: the country’s GDP warrants.

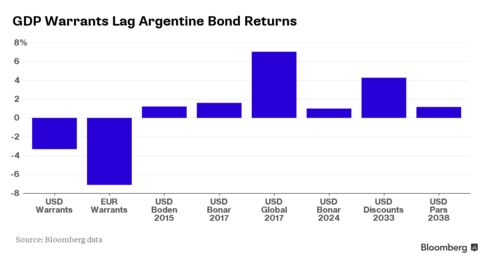

With the economy unlikely to grow enough to trigger payments on the securities anytime soon, the dollar-denominated warrants have dropped 3.3 percent in the past three months. The country’s euro warrants have fared even worse, tumbling 7.1 percent. Meanwhile, Argentina’s overseas bonds have gained 3.7 percent on average, the most in Latin America.

But keeping the warrants at arms’ length may no longer be in investors’ best interest, say Bank of America Corp. and Hapoalim Securities. They’re now recommending buying the securities as a bet that President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner’s successor will unwind policies that have fueled inflation and kept Argentina out of international bond markets for over a decade.

“The warrants offer an attractive risk-reward and are a nice way to gain exposure to the political transition if you missed the rally,” Jane Brauer, a strategist at Bank of America, said by phone from New York.

Brauer says the slump in the warrants is in part due to the outlook for Argentina’s peso, which is down almost 10 percent this year. Coupon payments would be smaller if the exchange rate weakens further. Bank of America estimates that at 8.4 cents per dollar warrant and 8.1 per euro warrant, investors will recoup the cost of the warrants by 2019, assuming no payments are made until 2018.

“They have been unnecessarily punished because FX uncertainty has driven excess risk premium, they have a non-traditional buyer base, and they are not in the benchmark index where dedicated emerging market investors are,” Brauer said.

She estimates the fair value of the dollar warrants is about 9.7 cents on the warrant and 10.7 for the euro securities. Bank of America expects the first payment will probably occur in 2018, which could total 4.4 cents per warrant, for growth in 2017 that will rebound to 3 percent. Holders will receive another payment of 4.9 cents in 2019.

Investors in the warrants receive a payment if growth in the previous year exceeds a preset threshold and the inflation-adjusted value of the country’s gross domestic product is above the base-case scenario laid out in the prospectus. Starting this year and until the warrants mature in 2035, the threshold will be 3 percent.

Economists surveyed by Bloomberg expect Argentine growth to fall short of the threshold until 2017, when the economy will expand 3 percent, according to the median estimate.

Economy Minister Axel Kicillof said Sept. 15 that the expansion in Argentina has picked up since the second quarter and is estimated to end the year at 2.3 percent. That would be more than five times the median growth forecast of economists surveyed by Bloomberg.

Bond investors are betting the new president will end Argentina’s battle with hedge funds led by billionaire Paul Singer’s Elliott Management Corp., a move that would pull the nation out of default and restore Argentina’s access to international markets. U.S. District Judge Thomas Griesa has blocked the country from honoring its foreign debt until the government reaches a settlement with creditors from its 2001 default.

Fernandez, who calls the investors “vultures,” has refused to comply with the ruling.

Front-runner Daniel Scioli and leading opposition candidate Mauricio Macri have both indicated they’d hold talks to end the debt dispute.

Ending the creditor battle would help “unlock foreign savings” and boost economic growth by as much as 4 percentage points, Buenos Aires-based investment bank Puente Hnos SA said in a July 23 report. Puente strategists led by Alejo Costa said that at current price levels, every percentage-point increase in potential GDP growth would increase warrant valuations by 30 percent.

For investors “looking to gain access to Argentine assets on expectations for a quick solution of the holdout case, these GDP warrants are worth considering,” Victor Fu, a New York-based strategist at Hapoalim Securities, said by e-mail. If the economy “can grow 2.3 percent for 2015, as Kicillof said, it should raise the GDP base for the future cash flows of the warrants.”