Sunday’s election of opposition candidate Mauricio Macri marks a moment investors have been waiting for in Argentina for a long time.

In the 14 years since the country carried out the biggest default the world had ever seen, international investors watched an economy that had long been one of their favorites turn into a pariah in global capital markets. Under the Kirchners -- first Nestor and then his wife, Cristina -- Argentina became best known for its byzantine foreign-exchange system, the seizure of privately-owned assets and the under-reporting of inflation.

All that could change now. Macri, a 56-year-old Buenos Aires native, is pledging to quickly reverse much of the Kirchners’ policies and open up an economy that’s posting back-to-back years of almost zero growth.

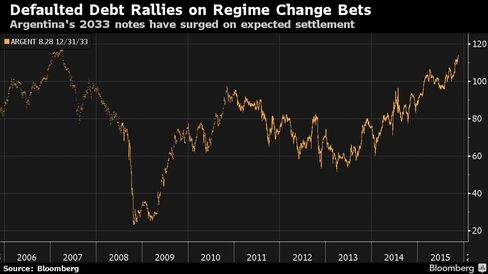

Investor excitement is tangible, a rarity nowadays in a region that’s suddenly fallen out of favor. Companies, including Germany’s BayWa AG and Brazil’s BRF SA, are prepping to expand their presence in the country and Argentina’s benchmark stock index soared 30 percent in the past three months as traders anticipated a Macri victory. Even the country’s defaulted debt -- the government fell back into default last year on legal grounds stemming from the 2001 debacle -- has been rallying, with prices on benchmark bonds climbing well over par value. Eager to reinsert the country in foreign markets, Macri has said that settling the old debts will be a top priority after he’s sworn in as president on Dec. 10.

“We are optimistic,” said Jody LaNasa, the founder of the $1.5 billion hedge fund Serengeti Asset Management, which owns Argentine securities. “The question is whether this is going to be something like the rebirth of Argentina or another failed dream that people get excited about, but then they can’t overcome the challenges.”

The challenges indeed are substantial: foreign reserves are at a nine-year low; prices on the country’s commodity exports are depressed; the budget deficit is soaring to the widest in three decades; and inflation, as tallied by private economists, is running at an annual pace of more than 20 percent.

Macri’s victory over the pro-government candidate, Daniel Scioli, is seen in part as an expression of Argentines’ frustration with the economy under the Kirchners. With 98 percent of the ballots counted, Macri, a two-term mayor of Buenos Aires and wealthy businessman, had 51.5 percent of the votes while Scioli took 48.5 percent. Minutes after Scioli conceded the race, Macri addressed his supporters, telling them that "a wonderful new stage begins for Argentina."

Argentine bonds extended their rally. The benchmark securities due in 2033 gained to a price -- which includes interest owed since last year’s default -- of 114 cents on the dollar, an eight-year high. The Global X MSCI Argentina ETF rose 0.5 percent in German trading.

The return to growth that his backers, and foreign investors, are anticipating won’t be immediate. If anything, analysts are warning that things could get worse initially as the new president implements the kind of tough measures -- cuts to the budget, a devaluation of the peso -- that figure to further choke off consumer demand. Oxford Economics says gross domestic product will likely contract the next two years before rebounding to post growth of more than 5 percent by 2019.

This is not the first time, of course, that foreign investors have piled into Argentina. In a country that was once one of the world’s richest (back around the turn of the 20th century), there have been countless booms and busts. Most recently, the nation became the darling of the investing world in the 1990s, when President Carlos Menem tamed hyperinflation, sold off state assets and opened up the economy.

At the height of that boom, Argentina posted back-to-back years of growth topping 10 percent. But mistakes were made too and the go-go days wouldn’t last. By the late 1990s, the rigid currency peg system that had worked so well in taming inflation years earlier was undermining economic growth. Hamstrung by the recession and unnerved by bloody protests sweeping Buenos Aires, the government defaulted on $95 billion of bonds in 2001 and devalued the peso weeks later.

The collapse fueled resentment toward free-market policies and propelled the Kirchners into office. That sentiment lasted long enough to allow Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner to succeed her husband in 2007 (and win re-election in 2011) but would ultimately fade too. Despite a surge in overseas prices for Argentine commodities during much of the past decade, the peso lost 70 percent of its value under their rule.

Now it’s Macri’s turn.

There’s no shortage of big-name investors -- George Soros, Daniel Loeb and Richard Perry, to name a few -- betting on him successfully resolving the debt dispute and regaining access to international credit markets. To pull that off, Macri will have to reach a settlement with the billionaire hedge-fund manager Paul Singer, who’s long refused to relinquish his bonds from the 2001 default at the deep discount that Argentina imposed on other creditors.

While the Kirchners couldn’t get themselves to negotiate with Singer, their long-time nemesis, most expect Macri to show no hesitation in initiating talks. What may ultimately prove a tougher test is trying to get a divided congress to back the austerity measures he wants to implement.

“I just worry about the political machine,” said Ray Zucaro, chief investment officer at RVX Asset Management, a Miami-based investment firm. Still, Zucaro said he’s optimistic. "We’re super positioned here, long and strong.”

Open all references in tabs: [1 - 3]